People say worship music sounds the same. They could mean something else.

The first time I taught Music History I, a student came to my office worried about an upcoming listening exam. “This is impossible,” he said. “All music sounds the same.”

That semester, we studied everything from ancient Greek music theory to Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. We cover Gregorian chant, Notre Dame polyphony, Renaissance madrigals, Counter-Reformation masses, and more.

The music spanned centuries. There are works in complete vocal unison, others with intricate harmonies. Some are in Latin, others in German. But college students don’t spend their time listening to chants and madrigals. I don’t blame them for having difficulty with the exam and I know that their displeasure and discomfort comes mainly from unfamiliarity.

So when I hear someone say, “All contemporary worship music sounds the same,” I think about my music history students and wonder if that person just doesn’t like music that much.

What does contemporary worship music sound like? Is it fair to say that everything “sounds the same”?

“(Almost) 100% of the top 25 worship songs are associated with just a handful of megachurches,” was the headline from a publication of Worship Leader Research at the beginning of this year. Most of the songs on the list were written or recorded by artists associated with Elevation, Bethel, Hillsong or Passion, “the big four.”

Because so much influence is concentrated in a small group of creators and organizations, the number of people creating the most popular worship music is small (and getting smaller). But does this concentration of influence and popularity mean that contemporary worship music is starting to sound the same? Or does it just sound like it’s part of the same genre?

Over the past 25 years, contemporary worship music has matured into a recognizable musical style and industrial force, with its own conventions and characteristics. A few decades ago, “worship music” was considered a subgenre of CCM or a set of music marketed primarily to churches and worship leaders.

Now, the genre is different within the world of Christian music and the mainstream music industry. Worship albums have their own category at the Dove Awards; Spotify has multiple curated playlists dedicated to the genre. Like most genres, contemporary worship music has a small group of influential stars (the Big Four) who reliably produce its most popular hits. The songs don’t sound the same, but they sound like they’re together.

“In any genre, there will be key markers,” said Shannan Baker, a member of the Worship Leader Research team and a postdoctoral fellow in music and digital humanities at Baylor. “There are similar themes, text devices like ‘broken chains,’ but the deeper you get into the music, the more you hear the differences and pieces that make certain artists unique.”

“Everything sounds the same” is an easy criticism of any musical genre, and it usually stems from disgust. “All country music sounds the same” is a way of saying “I don’t like country music.” Those who don’t prefer that particular genre probably imagine it according to their own generalized perceptions of its characteristics—twang, steel guitar, something about trucks or dirt roads.

Those who spend more time listening to a genre, as Baker points out, recognize the diversity it contains. There is obvious musical variation in the songs on the researchers’ top 25 list. “This Is Amazing Grace” (Phil Wickham) is an upbeat four-track with a rhythmically simple, singable chorus. “Oceans” (Hillsong UNITED) begins with a quiet, sparsely accompanied verse and chorus often performed in a slow, flexible tempo to showcase an expressive vocalist.

“Reckless Love” (Bethel Music, Cory Asbury) is in a minor key and is in 6/8 time. Passion’s energetic “Glorious Day” begins with a faint guitar verse, “I was buried under my shame,” and builds anticipation until the belted out chorus, “I run out of that grave.”

Perhaps part of the “identity” perceived in worship songs arises from the presence of common themes and Christian truths.

“There is an underlying hope that the Gospel allows,” wrote Nick Lannon, an Anglican pastor in Kentucky in an article for Mockingbird, “Why All Christian Music Sounds the Same (Even When It Doesn’t)”. “The beats and lyrics may change, but you’ll feel like you’re listening to the same song…and it’s instantly recognizable.”

It’s true; The rhythms, melodies and lyrics vary, as they do in any genre, but themes such as love, grace and hope are consistent. And a variety of common musical characteristics may not be perfectly consistent, but a combination of them can place a song in the genre.

Contemporary worship songs often contain a clear demarcation between verse and chorus, a climactic bridge, simple harmonic structureand heavy use of pads and keyboard effects to create a washed-out texture base. Dynamic contrast and vocal range guide singers and listeners through moments of reflective calm and celebratory exuberance (as on “Glorious Day”).

These devices and harmonic language are not exclusive to contemporary worship music; The genre is largely based on pop, rock and country. And given a recording by one of the Big Four, it’s not certain that Bethel or Elevation’s music would be instantly recognizable, aside from perhaps the voice of a vocalist known as Kari Jobe.

One thing that distinguishes contemporary worship music as a genre is its purpose and function: facilitating worship. And the genre has evolved to reflect the musical practices of a particular type of worship community, shaped by its most popular artists.

There are audible clues in sacred music recordings that point to what type of religious practice and gathering space they are for: a gospel choir or an organ, for example. Contemporary worship music in the vein of the Big Four borrows from mainstream pop and rock; the instrumentation (synths/keyboard, electric guitar, drums, bass) tells the listener that this music is for churches with a rock band setup.

Beyond these important means of worship, popular artists such as Keith and Kristyn Getty, Sovereign Grace, and CityAlight write music that uses similar instrumentation but draws more inspiration from the musical structures and text-writing style of 18th- and 18th-century hymns. XIX. And yet, music from this segment of the niche still seems comfortably placed in the “contemporary worship music” genre.

Someone who claims that “all worship music sounds the same” might be thinking beyond the actual sound of the songs to a broader perception of sameness or monoculture around contemporary worship.

All musical genres can feed and adhere to their own. subcultures and communities, which use the musical body to project an identity. The same goes for worship music today, to some extent, where fans are also drawn to personalities, fashionand the aesthetics that accompany it.

For some worship leaders and church musicians, the music of Bethel, Hillsong, and other popular worship artists has been associated with engaging, Spirit-filled worship. This music often comes with professionally produced visual media on platforms like YouTube and Instagram, so the songs are attached to images that tell viewers what kind of worship experience the music can create: how it looks and feels, how the worshipers will act.

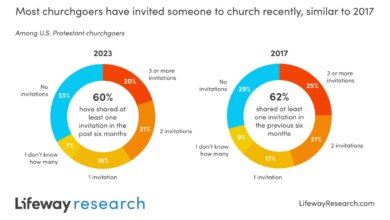

TO worship leaders survey found that more than half of respondents said they sometimes wished their church’s worship style/musical culture was more like these artists.

“It wasn’t just about the band and the music sounding a certain way,” Baker said. “It was about wanting their congregations to participate physically and visibly.”

Marc Jolicoeur, another member of the Worship Leader Research team and a worship and creative arts pastor in New Brunswick, Canada, says many worship leaders aspire to recreate some aspects present in videos and sound recordings because they have had deep, first-class experiences. hand with music (at conferences or concerts, for example) and want to share it with their local churches.

“We thought: I want that for my people, for my local church and my congregation,” Jolicoeur said. But it’s not about wanting flashy production and professional quality for their own sake. It is about the power of a particular model and culture of musical worship.

For many American Christians, worship conferences and concerts are places where we have experienced moving, dramatic, and emotional worship. It is therefore not surprising that these stages and the music they host have become models to which leaders and musicians aspire.

The music of the Big Four and other popular worship artists does not sound the same, but it does evoke these desirable “mountaintop” worship experiences.

Perhaps if there is any danger of “identity” in today’s most popular worship music, it is in the narrow view of what meaningful musical worship can or should be. Not all songs sound the same, but the genre’s conventions increasingly depend on access to multitracking, a big sound system, and an entire team of musicians. For most churches, Sunday morning worship is nothing like a stadium concert.

Leaders who want to use popular worship hits face the challenge of adapting and reinventing these songs for their local churches. The process requires creativity, flexibility, and a willingness to let go of some of the audiovisual associations that a particular song carries.

Adapting music to the local church and its particularities has always been the task of a music minister or worship leader. And, Jolicoeur says, the balance between pursuing excellence or musical ideals and recognizing the needs of his congregation is part of the calling.

Worship leaders “just want to create an environment where people are free to experience Jesus.”