Tradwife Content Offers Fundamentalism Fit for In…

Let’s bring back beauty,” begins the caption of a viral reel on Instagram.

The clip features Christian influencer Katie Calabrese in an airy long dress followed by a montage of images: flowers on an open Bible, a clothesline full of linen neutrals, a clean stairwell with wooden floors and shiplap walls, a faceless woman standing in front of a bowl of dough while holding a baby.

The caption lists other things she wants to bring back: “ladies who know how to whip up a delicious meal for unexpected guests,” going to church, having big families, and “loving your husband and singing his praises in front of others.”

Calabrese belongs to a cohort of online “tradwife” influencers, whose personas are built on the revival of various “traditional” expressions of femininity, marriage, homemaking, and family life. The thrust of their callback message rings familiar to those who grew up in fundamentalist Christian circles, though it’s uniquely packaged for Instagram and TikTok, where tradwife posts have grown substantially since 2020.

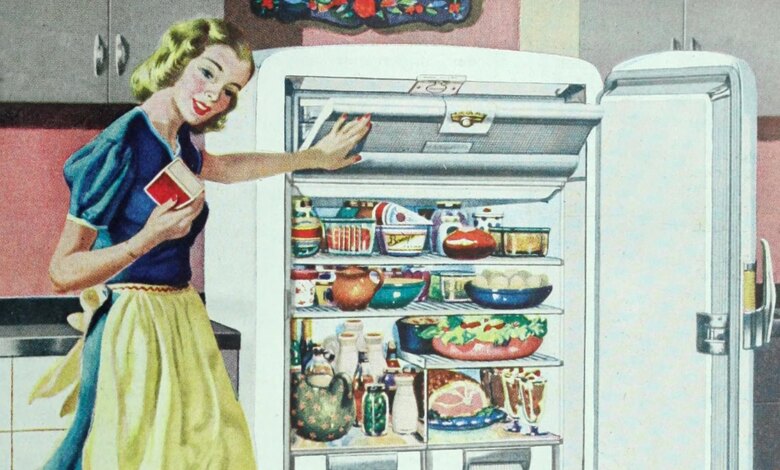

Tradwife content is unabashedly ahistorical, drawing on ideas and imagery from across time periods. Some tradwives build their brand with a 1950s June Cleaver persona, wearing lipstick and an A-line dress to do housework. Others evoke imagined versions of Little House on the Prairie: long dresses, rustic homemade bread, and rural homesteads. Some posts borrow painted images of Victorian households or Regency-era social gatherings.

Unlike other influencers who create content about homeschooling or homesteading, a tradwife influencer makes faithfulness to some aspect of “traditional” womanhood a central tenet of their online brand and identity. It’s a subtle distinction, but not every influencer online who wears long dresses and bakes sourdough fits in the tradwife category.

“The tradwife trend looks to a mythic past where everyone knew their role,” said Emily McGowin, associate professor of theology at Wheaton College and author of the book Quivering Families: The Quiverfull Movement and Evangelical Theology of the Family.

“We’re in a time of confusion and ugliness. People are looking for something beautiful and appealing, a time when things were simpler, even though we know things weren’t actually simpler.”

Many tradwife influencers are also believers who foreground their faith, making a case for “biblical womanhood” through their stylish and meticulously curated feeds. Even creators who don’t consider themselves religious are pitching a vision and worldview that many Christian women—particularly evangelicals—eagerly cosign.

Gender ideology is at the core of what it means to be a tradwife. It’s not surprising that evangelical women are drawn to content that affirms gender distinction and positions women in service to their families and their husbands—as are Catholics and Mormons, as well as some New Age agnostics and socially conservative, religiously unaffiliated “nones.”

Evangelicals and Mormons come together in the tradwife space, sharing a vision of family life, marriage, modesty, and religious liberty, despite stark theological differences.

When Mormon tradwife Hannah Neeleman posts a video of her family of ten getting ready for church on her “Ballerina Farm” Instagram account, evangelical followers can set aside their objection to the kind of church because the vision presented has very little to do with doctrine and corporate worship practices.

It may be that fundamentalism, rather than a particular set of Christian beliefs, is the common ground that unites the tradwife empire.

Columnist David French recently described fundamentalism as a psychological posture marked by certainty, ferocity, and solidarity. Tradwife content and the communities of followers that gather around these influencers offer all three: certainty in a more fulfilling, God-ordained way to be a woman, wife, and mother; ferocious and persistent advocacy for a particular lifestyle and perfectionistic commitment to its aesthetics; and solidarity with the millions of fellow followers who like, comment, and share.

Separatism, a life set apart, is baked into the pitch that tradwife content offers, appealing to Christians who want to be “in the world, but not of it,” modern-day Proverbs 31 women. These influencers are attractive models for those who want to dress, feed their families, educate their children, or clean their homes differently than we expect in 21st-century American society.

Women who grew up in fundamentalist religious contexts recognize the parallels in tradwife content. It’s selling a lifestyle that they have experienced firsthand, marketed to them by their churches and faith communities.

They see it as a new way to spiritualize hyper-feminine womanhood and strictly defined gender roles. It’s content they have seen before, repackaged for a new generation.

“These images of simple beauty and slow living aren’t real,” said Abbi Nye, an archivist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, who grew up as the oldest of nine children in a Latter Rain Pentecostal church in upstate New York.

Before Instagram, Nye pointed out, there were magazines aimed at conservative Christian families like Above Rubies and Vision Forum (from the organization of the same name). Their nostalgic and sentimental stories encouraged women to consider staying at home, homeschooling, gardening, and keeping an open womb.

Nye said that families in her church were trying to live the life tradwife influencers model online, but that it put women and children in a vulnerable position. Almost everyone was struggling to make ends meet.

“The tradwife content we see online comes from people with a lot of money. In my community, most people were living below the poverty line,” said Nye, who runs an advocacy network for survivors of abuse from her religious community. “It makes me angry because I know that the image being presented is false.”

Recent reporting on tradwife influencers has noted that the trend’s standard-bearers are quite wealthy. Neeleman is the daughter-in-law of the founder of JetBlue. Ballerina Farm is a lucrative business, and the account has nearly 9 million followers on Instagram, where you can watch Neeleman bake, milk the cow, or compete in the recent Mrs. World pageant.

Tradwife influencers who don’t have Neeleman’s wealth may still try to project the impression of idyllic lives and homes. Calabrese’s post about “bringing back beauty” is composed of images she found on Pinterest (which she acknowledges in the caption).

Author Tia Levings, featured in the recent documentary series Shiny Happy People, says that tradwife content is just a new incarnation of the media and books that brought her into the “trad” life in the mid-’90s.

Levings attended churches and conferences where she learned about the dangers of vaccinations and pediatricians, the value of canning to build an end-of-days pantry, and how to mail-order birth kits and herbal remedies. Magazines, catalogs, and homemade pamphlets circulated to help women envision a purer, set-apart existence.

The April 2009 issue of Above Rubies features a two-page spread on sourdough bread (a mainstay of today’s tradwife influencers) and an article titled “How to Fight Like a Woman,” which entreats women to “cry like a warrior” because “tears are unique to women and tears move God to battle.”

The article accompanying a sourdough recipe could be pulled from the caption of an Instagram reel, singing the praises of “homemade, artisan, organic, succulent, sour dough, ancient grain bread,” free of the phytates that “make your bread very hard to digest,” but also warning, “if you are over 30 and don’t have a Speedy Gonzales metabolism, don’t reach for more than two pieces at one sitting.”

The design of Above Rubies lacks the aesthetic polish of today’s viral Instagram content, but the magazine is clearly trying to reach women with the same messages: The world around you—the food, the schools, the media—isn’t as it should be. You, as a woman, can make your household different.

“The message isn’t any different,” said Julie Ingersoll, professor of religious studies at the University of North Florida. “The medium is different, and that has some impact. But when you look at earlier media, its roots are recognizable.”

Rebekah Hargraves’s family joined a Reformed family-integrated church near Chattanooga, Tennessee, during her teen years, and they were quickly won over by Vision Forum’s catalogs and media.

Hargraves and her father attended father-daughter conferences, where men spoke on the value of being a stay-at-home daughter and giving up career aspirations in order to fulfill a higher calling.

“My family was ripe for the picking in some ways,” said Hargraves, now a writer and blogger who homeschools her two kids. “My mom had this dreamy picture of returning to the past. My great-grandparents had a farm. We all had this romanticized view of that lifestyle.”

Hargraves had always been homeschooled, but life at home began to look different as the family adopted the ideals touted by books like So Much More, a survival guide for young women living in a “savagely feministic, anti-Christian culture.”

“I went from thinking, Wouldn’t it be nice to wear long dresses? to believing that it was a sin not to,” said Hargraves.

Before joining their new church, she had dreamed of working in publishing—specifically for Lifeway, the Southern Baptist Convention publisher. But the new vision of womanhood set before her seemed to require her to let that dream go.

Levings, whose parents were Midwestern entrepreneurs, grew up believing that she could have a career and be a homemaker, but as a new mother, she was won over by the suggestion that dedicating her life to her home and family was her highest calling. She believes that tradwife content, old and new, offers many Christian mothers something they desperately want: affirmation and acknowledgement.

“Moms are exhausted, so the beautiful aesthetic is part of what helps drive women back home. Why not garden and can? And it all happens to be pretty,” said Levings. “Scrubbing your floors becomes a holy act. You’re fulfilling the Great Commission through motherhood.”

For Levings, romanticizing mundane homemaking tasks seemed like a way of honoring and elevating that work as the only worthy option for women. The sense of righteous purpose and certainty was powerful. It was her way of participating in the dominionist project of winning the world for Christ. And for a while, it kept Levings committed to her role.

“It feels like you’re making a positive, proactive choice for your home and your family,” said Levings. “But I was so isolated and alone in my little suburban house. All it left me was really lonely.”

Christian tradwife influencers offer up their lifestyles, families, and homes as inspiration, but also as evidence that a commitment to their version of “traditional” femininity yields good, beautiful things. The content is winsome; it’s supposed to be. The underlying implication is that the lifestyle is in line with God’s design and intention for women and their families. The combination of aesthetics and spiritual mission makes that message especially urgent and potent.

“We were very aware that we were proving something,” said Abbi Nye, adding that her pastor’s wife instructed families to view their conduct and appearances as a witness to the world. “The reason we were dressing in nice clothes was to make Jesus attractive to the world. We had to prove that homeschooling was the best, that our church was the best, that this was the best way.”

Their mission included not only proving the superiority of their separatist lifestyle but also their commitment to clearly defined gender roles and hierarchy. Feminism was the enemy, just as many present-day tradwives say they offer an alternative to failed “girlboss” feminism.

The certainty, ferocity, and solidarity that Nye, Hargraves, and Levings experienced eventually gave way to the realization that an abstract vision of traditional femininity and family life did not deliver on promises of a beautiful, comfortable, peaceful life. It also started to break down as they encountered Christian women who were doing things differently.

When Hargraves enrolled in a ballroom dancing class for homeschoolers as a 17-year-old, she was shocked by a peer who was wearing shorts. “But she had this light about her,” said Hargraves. “And I couldn’t reconcile how someone could have Christ and be wearing shorts.”

That encounter shook her confidence in the righteousness and superiority of her family’s lifestyle, and she looks back at it as the beginning of the unraveling of her commitment to a “trad” life.

“It planted a seed of doubt. It made me uncomfortable, but I couldn’t ignore it. I thought, Maybe I’m wrong, something’s just not adding up.”

For some Christian women, the tradwife model seems to offer an ideal way to live out biblical womanhood, but the fundamentalist orientation of much of the content implies that there is one ideal, one “God’s best” for women.

Even conservatives who ascribe to certain gender roles as biblical have cautioned against presenting or viewing the tradwife aesthetic as the Christian standard.

“Obviously there is nothing wrong with living on a farm and making your own sourdough and homesteading and all of those wonderful things, but because this has become a trend on TikTok and social media unfortunately some people have made the mistake of conflating that so-called trad life and being a tradwife with being a biblical wife,” said commentator Allie Beth Stuckey at last month’s Founders conference. “There are biblical standards, of course, that women are called to, but they are not standards that are set by social media.”

Defenders of creators in the space say that tradwives are expressing themselves, building businesses, and putting out content that serves their audience. Still, faith-forward tradwife content makes significant claims and implications about the theology of gender.

“Our theology of gender matters quite a lot,” said McGowin. “But when Jesus preaches the gospel, he doesn’t talk about how we are performing our gender.”

While the gospel of tradwife content claims to offer women a different and better way, those who have lived through the previous iterations know that fundamentalism and legalism may promise freedom but end up with a vision that, while pretty, is ultimately narrow and confining.