It’s the End of the World (But Not as We Know It)

Next week’s solar eclipse has stoked the flames of end-time speculations, once again whipping doomsday theorists into a frenzy.

As the April 8 event will take place primarily over North America, some in the US are anticipating a great Day of Judgment complete with terrorist attacks, biological warfare, and nuclear meltdowns. According to alt-right conspiracy theorists, including some fringe evangelical leaders, this war will usher in a new world order in which Christ will return and America (alongside Israel) will rule the nations.

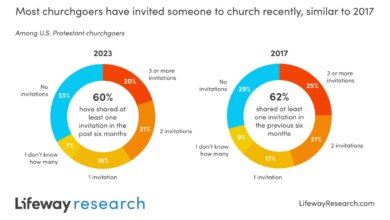

This isn’t the first time apocalyptic predictions were based on impending eclipses—the same thing happened in 2017. But end-of-world interest seems to have increased over the last few years, as things like the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the Israel-Hamas conflict has meant nearly every region of the globe has faced some sort of calamity. These and other recent tribulations have led many believers to conclude that the end is near. In fact, a Pew Research Center study found in 2022 that over 60 percent of evangelical Christians in the US believe we are living in the end times.

But while some passages in the Bible do link astronomical phenomena with “the end” (Matt. 24:29; Joel 2:31), doomsday prophets fail to explain why their biblical, global, and cosmic calculus often revolves around America. They further neglect the fact that an eclipse happens somewhere on Earth approximately every 18 months—and that these solar events have been associated with imminent doom for thousands of years without consequence.

And yet, based on the Book of Revelation, end-time conspiracists are correct in one aspect of their eschatology: We are living in the end times. But not, perhaps, in the way they might think.

Empowering every generation to see signs of “the end” is precisely the brilliance of the last book in the Bible, which contains the most direct and sustained teaching on the end times in Scripture. John, our apocalyptic author, has masterfully woven together a series of symbolic visions that readers of any time can understand in their own context. Above all, Revelation vividly communicates the gospel message and how Jesus expects us to respond in the here and now—which is why it is just as crucial to our faith as the Gospels.

John teaches that the end is near—so near that it’s already here. Christ’s death and resurrection has inaugurated the last days (1 John 2:18; Heb. 1:2; Rev. 1:1–3), and only the Father knows when Jesus will return (Mark 13:32–33)—which means we don’t have to “decode” Revelation or pinpoint apocalyptic events. Yet this is precisely what many of its interpreters have tried to do.

One of the most popular Christian interpretations of the end times is Left Behind—a series franchise portraying the believers’ Rapture and the subsequent labyrinth of events. Although few are still talking about the books, and it’s been a decade since the last movie came out (which was criticized by CT’s own review and follow-up), the series has “left behind” an evangelical legacy of misinterpreting the Book of Revelation and its apocalyptic vision.

The first Left Behind novel was published a scant few weeks after I became a Christian in 1995, and at first, I consumed the literature with almost as much reverence as Scripture itself. But as I kept reading the series, my interest waned. It seemed to offer little substantive guidance for my burgeoning faith. So I concluded that the Book of Revelation, upon which the books are loosely based, must have little to offer as well. After all, if I was going to be raptured before all the frightening events of the Great Tribulation, why should I care about John’s apocalyptic vision?

But now, nearly 30 years later, I’m a Bible scholar who specializes in the study of Revelation, and I continually implore people to not misuse the book as fodder for such end-times predictions.

The most common way God’s people have distorted John’s Apocalypse is by correlating its visions with real-world events, and so misconstruing its primary message. In every period of history, God’s people have identified signs of “the end” and the nefarious forces that would bring it about. In fact, the end of the world has been variously calculated as the years A.D. 275, 365, 400, 500, 999, 1000, 1666, 1843, 1914, 1994, and 2000, just to name a few.

The problem is, there are real-world implications for these apocalyptic forecasts—especially when they are more informed by a political stance than by a responsible study of the Scriptures.

During the Crusades in the Middle Ages (A.D. 1095–1291), Western Europeans hoped retaking the Holy Land would usher in the return of Christ—and multitudes of Muslim and Jewish people were slaughtered in the process. A couple hundred years later, Protestant Reformers maligned the papacy of the Catholic church as the Antichrist. Soon after, American colonists sought to establish a “New World,” which was closely identified with the New Jerusalem of Revelation 21. Thus, England was seen as the “Beast,” and the British Stamp Act became his mark.

In the 1980s, apocalyptic thinking vilified Russia as an “evil empire,” who, along with China, was identified as Gog and Magog (Rev. 20:8)—vicious enemies who will come against God’s people (and/or Jerusalem) before (or after) the Millennium. Today Iran and Palestine are two more contenders for the Gog and Magog title. At the same time, some among the Russian Orthodox faith believe that America leads the forces of the Antichrist.

My point is that if you are reading the Book of Revelation looking for specific details—a date for the world’s end, the name of an antichrist, or nations to label as enemies of God—you’ll find them. There have always been, and there will always be, forces that oppose God and his people.

But it’s important for us to understand the underlying eschatology behind narratives like the Left Behind series, since it lingers on in the evangelical consciousness and colors the lens through which many still read and interpret the Book of Revelation. One key facet of this worldview is dispensational premillennialism, which holds that true believers will be raptured—or supernaturally transported—to heaven, prior to seven years of intense geological, social, and political upheaval during which the Antichrist will rise and the Jerusalem temple will be rebuilt.

This period, “the tribulation,” will conclude with a great final battle, Armageddon, after which Christ will return and reign on earth with his saints for a thousand years. And although we don’t have space to unpack all the problems with this interpretation, it should be noted that the major tenet of this teaching, the Millennium, is only mentioned in one highly disputed passage of Scripture (Rev. 20:1–7). But exegetical issues aside, what are the potential dangers of this thinking in practice as we daily seek to live out the gospel?

First, if we take this mindset to its logical extent, we run the risk of ignoring our most sacred calling: loving all our neighbors. Viewing other people or groups as the divinely foretold enemies of God absolves us from attempting to reach them with the gospel message. In other words, if the Bible predicts that a person or a group of people are going to be defeated by Christ and burn in the lake of fire (Rev. 20:11–15), who are we to say otherwise?

Instead, Revelation teaches us that our cruciform witness bears fruit and serves as the vehicle by which those who reject God repent and give him glory (Rev. 11:13; 21:24). When we live out the gospel in a broken world, we embody a better way of life—the truth that God is liberating his entire creation from the forces of sin and death.

Second, if we expect to be raptured prior to trials and tribulations, we won’t be prepared when they smack us in the face. A major facet of Revelation’s teaching is that disasters are going to occur time and again. In every age, God’s people will face geological, political, social, and personal calamities. But if we assume Christ will exempt us from such affliction, our faith can wither when we encounter it. Instead, John seeks to fortify our faith as he exhorts us to persevere through trials. We aren’t called to escape the world, but to bear witness to Christ in it.

Third, closely associated with “Left Behind” thought is the belief that the national/political entity of Israel enjoys a status that trumps that of other peoples and nations—in part because of the association of Zionism with American exceptionalism throughout modern history.

But the overwhelming teaching of the New Testament, including Revelation, indicates that all the peoples of the earth are equally treasured by God. The Father desires every people groupto experience his love and grace through Christ (Acts 10:34–35; 2 Pet. 3:9). Biblically and theologically speaking, no national entity, including America and Israel, receives special favor in the eyes of God. And to say otherwise can greatly hinder the spread of the gospel in the world.

With the increasing polarization of the United States and with traditional Judeo-Christian values often being denounced as white nationalism, it is vital for us to affirm that the teachings of Scripture, the salvation of God and his promises are equally available to all peoples. Such a principle is not arbitrarily imposed upon Scripture but arises directly from sound exegesis.

If the point of Revelation isn’t to give us a map of end-time events, what is it for and why do we need it? The purpose of Revelation is to motivate believers through a message of hope. Jesus has already defeated evil! We aren’t waiting on the Rapture, the Antichrist, or Armageddon. We are waiting for Jesus. Out of his love and grace, God may tarry—but when Jesus finally returns, he will come triumphantly to judge evil as well as reclaim and renew God’s creation.

In the meantime, believers continue to “war” on his behalf—not against flesh and blood but against the unseen powers of this world (Eph. 6:12). And our victory is achieved paradoxically through suffering and self-sacrifice. Just as Christ accomplished the redemption of the world through his sacrificial death, so also Christ’s followers are called to become instruments of restoration through our own cruciform obedience and perseverance.

The means of victory in the Apocalypse is both counterintuitive and countercultural. The idea of a future Rapture, in which believers escape tribulation by being supernaturally transported to heaven, completely misses the point of the book. Even worse, expecting Christ to return at the end of time to defeat his enemies through earthly warfare is to make the same mistake as the first-century Jewish people who expected their Messiah to overthrow Rome.

To place our hope in a Messiah who wins through superior power and military might is to agree with the ideology of this world rather than that of the slain-yet-standing Lamb. The Messiah we follow is the one who conquered by means of a humiliating, painful, and public death.

All this rich teaching is lost when we see Revelation as a series of events to decode. Reading the book through any other lens than its own severely impedes our ability to embrace its missional and spiritual significance. So how do we avoid this pitfall and appropriate the message of Revelation in a way that edifies our faith, transforms our theology, and benefits God’s creation?

First, we must study Scripture contextually. If we read Revelation in the context of the Gospels (and the rest of the NT), the image of a militant messiah who returns to slaughter his foes is nonsensical. We must also take the book’s genre into account. Revelation is apocalyptic literature, which contains symbolic communication, allowing us to see reality from a different perspective. An apocalypse doesn’t tell us about the end of the world but does something far more important: it reveals the true nature of the world.

In fact, the English word apocalypse stems from the Greek word apocalypsis, which means “a revelation,” not “the end of the world,” as it has come to mean in vernacular English (which, of course, is why the name of John’s book was translated as “Revelation”). And if that weren’t enough to convince us, John himself tells us that his visions are symbolic (1:1), a nuance that is often obscured in English translations. (The Holman Christian Standard Bible comes closest to the precise meaning with the translation that God “signified” the message to John, with a footnote that he “made it known through symbols.”)

Second, seeing reality from God’s perspective should galvanize our mission to the world. John’s message of victorious perseverance in the face of hostility was initially intended to reorient the identity and purpose of early Christians under the dominion of Rome—exhorting them to overcome the pressure to compromise with a pagan society. In much the same way, we should be motivated to embody the truth of the gospel in a world that rejects Christ and his kingdom.

John teaches that God opposes evil and fights on behalf of justice, and that he will one day decisively defeat all forces of darkness in the earthly and spiritual realms. But for now, God chooses to work primarily through the church and his saints. So, we should publicly fight for truth, goodness, and righteousness and oppose all falsehood, injustice, and evil on behalf of every people group. And we must resist the temptation to align ourselves with ideologies that are socially popular or politically expedient, even if we end up facing persecution for our refusal to join the bandwagon—knowing we’ll be ready for every trial.

Lastly, solar eclipse or not, we are called to live every day as if it is our last. And whether Jesus returns in a day, a month, or a thousand years, we are called to publicly speak and sacrificially embody the truth of the gospel. We can’t know the day or hour, but Scripture says Jesus’ return draws closer with every passing day (Matt. 25:13; 1 Pet. 4:7). Such a biblical truth should realign all our activities, goals, plans, and relationships this side of eternity.

We are, living in the end times. So, what are we going to do about it?

Andrea L. Robinson is a professor at Huntsville Bible College, an interdenominational speaker, and the author of numerous publications on Revelation, eschatology, and ecotheology.