‘City on Mars’ explores the dangers of colonizing the cosmos:

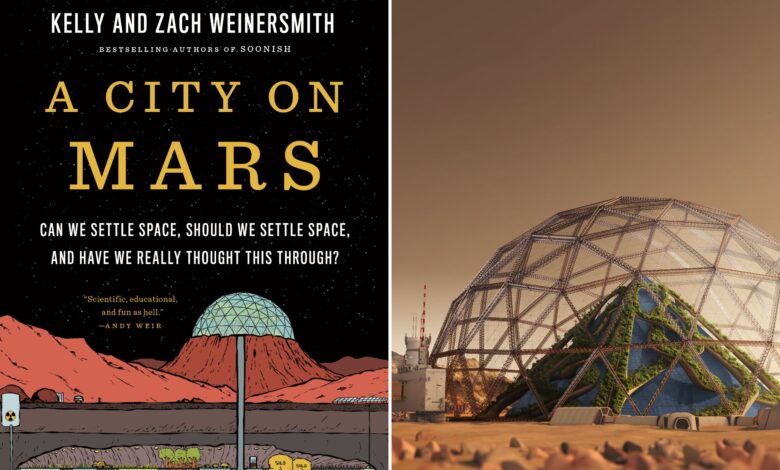

Space agencies, big corporations, and media-savvy billionaires (ahem, Elon Musk) have promised that building colonies on the surface of Mars will “fix almost everything” and give humanity the chance to “try something completely new and let everything behind.” the bad that lies behind it,” write Kelly and Zach Weinersmith in their new book, “A city on Mars: Can we colonize space? Should we colonize space? Have we really thought this through?” (Penguin Press).

But colonizing the red planet and building a new civilization there could be far from possible, and not even desirable.

“Public discourse on space colonization is filled with myths, fantasies, and a complete misunderstanding of basic facts,” write Kelly, a biologist, and Zach, a cartoonist.

But most of what you know about rocket science is probably wrong, or at least incomplete.

Even if you have read all the articles and all the books and seen all the documentaries about the future of space settlements, the vast majority of what exists has been “created by defenders for space colonization,” the authors write. They are biased sources who want to believe whatever they want. you believe.

The Weinersmiths admit that Mars, at the very least, has the potential to become an independent second home for humanity. And companies like SpaceX and rival Blue Origin, despite their respective overvaluations, are at least on the right path.

They have “genuinely revolutionized space launches and all of Earth’s space agencies,” they write. “The evidence is that they really believe in a future of space settlements.”

But faith doesn’t always translate into results, even for billionaires with infinite resources and unlimited enthusiasm.

So the Weinersmiths set out to find all the ways space settlements could work and the countless ways they couldn’t.

“It turns out that when you just talk about technical aspects like the size of rockets or whether Mars has water and carbon, the picture can seem pretty solid,” they write. But, “when you get into the softer details of human existence, things start to seem, well, soft.”

For example, we know very little about the long-term effects of space on the human body.

“Literally no one has been in space for more than 437 days in a row,” the Weinersmiths write.

Although the Apollo astronauts did not suffer any physical consequences from their missions, they were also a very small sample group: exactly twenty-four men, all of them test pilots in peak physical condition who together spent less than a month on the lunar surface. .

“If life in partial gravity has serious negative effects,” the authors write, “they will probably take longer to appear.”

In addition to the possibility of developing cancer due to the enormous doses of additional radiation outside the Earth’s magnetosphere, life in zero gravity will invariably lead to degradation of the spine, resulting in osteoporosis, weak muscles, back problems and other uncomfortable problems.

“All that lost bone calcium can contribute to constipation and kidney stones,” the Weinersmiths write.

By moving to Mars, he has “left the cradle of Earth for the nursing home of orbit.”

Basic necessities like food and water would have to be shipped from Earth, at least at first.

If you think food prices are expensive now, wait until potato salad has to be “propelled out of Earth’s gravity well, launched through the vacuum, and then gently deposited outside a Martian airlock.” , write the authors.

Other nutritional options could include bioreactors that produce meat from cells, insect protein sources (prepare for insect goulash), and possibly gardening, once we understand how microgravity and space radiation impact plants.

None of this will taste as good (especially insects) because “the space environment reportedly makes food taste less tasty,” the Weinersmiths write. “This may be a result of the fluid shift creating cold-like pressure in the sinuses, or it may be that in zero gravity odors don’t reach the nose, or it may be something to do with the artificial atmosphere.”

If all else fails, there will always be cannibalism, as Dr. Erik Seedhouse speculated in his 2015 tome “Survival and Sacrifice in Mars Exploration.”

Once the food runs out, Mars colonists will surely notice the “chunks of protein-rich meat living alongside them,” Seedhouse writes. Compared to waiting for Earth’s latest food delivery, with essential items at a staggering price (assuming it reaches you before you starve), eating the guy next to you may seem like the more practical solution.

What about sex in space?

“The physics will be a bit complicated because every action has an equal and opposite reaction,” the authors write. “There is no significant ceiling or bottom in zero gravity, at least in the physical sense.”

They note that G. Harry Stine, engineer and well-known popularizer of space science, has suggested that NASA has carried out “clandestine experiments,” confirming without a doubt that “it is really possible for humans to copulate in weightlessness.”

Stine also learned from an anonymous source that sometimes a “third swimmer” is necessary during space sex to “push at the right time and in the right place.”

The setup is reportedly known as “Three Dolphin Club” and there is supposedly an unofficial membership pin for those who have participated.

“Starting in 1990,” Stine wrote, there were “unscheduled personal activities aboard the space shuttle on seven flights.”

Even if an astronaut manages to carry out the Three Dolphin Club, there are no guarantees that the species will continue.

SpaceLife Origin, a Dutch startup dedicated to sending a pregnant woman to space, collapsed in 2019 after its CEO cited “serious ethical, medical and safety concerns.” Even if a baby could be born safely in space, she still has to grow up in a high-radiation, high-carbon dioxide atmosphere without gravity, which isn’t exactly an ideal situation for a developing human body.

Another potential problem: the alien turf battle.

The pro-Mars contingent maintains that space settlements will mean fewer turf wars, since there is plenty of room in space to call home.

No, the Weinersmiths write.

“Nations do not fight for land, but for particular land,” they write. “You cannot resolve disputes over Jerusalem, Kashmir or Crimea by promising the parties that these are equally large expanses of Antarctica.”

Furthermore, not every square inch of Mars is habitable and some parts are much more desirable than others.

If you think concerns about immigration are bad on Earth, wait until you get to Mars.

“Regardless of what you think about immigrants coming to your country, one thing you probably don’t fear is the possibility of them breathing too much air,” the Weinersmiths write.

But despite all these obstacles, the authors sum up the real reason we should probably avoid venturing to Mars to start a new life in two words: “Space sucks.”

“Space is terrible,” they write. “All of it.”

The soil of Mars is “laden with toxic chemicals, and its thin carbonaceous atmosphere causes dust storms around the world that block out the Sun for weeks at a time.”

It’s so terrible that even if Earth became nearly uninhabitable due to climate change, nuclear war, and zombies, it would still be a better home than Mars.

“To stay alive on Earth you need fire and a pointed stick. Staying alive in space will require all kinds of high-tech devices that we can barely make on Earth.”

This doesn’t mean we should avoid space entirely. Daniel Deudne, a professor of political science and international relations at Johns Hopkins University, has argued that “the existentially safest course of action for humanity is to simply never create a significant human presence in space,” the authors write.

What is different from No space activity.

“He just thinks it should be used for non-hazardous things, like science, environmental monitoring, and communication,” the Weinersmiths write. “Not the sprawling space exploitation regime of many geek fantasies.”

But it’s also unlikely to result in a colony full of Mars colonists with bad backs, confusing sex lives, and diets rich in insects (and possibly each other), fighting for limited oxygen with space immigrants in a new world order of the that no one is really sure who. S control.

The Weinersmiths do not believe that space settlements should never happen. It could simply be “a project of centuries, not decades,” they write. “We should take a ‘wait and go’ approach. “Expect great advances in science, technology and international law and then move many settlers at once.”

There’s a quote that space enthusiasts love to quote, from the founding father of rocketry, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. “The Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot live forever in the cradle,” he wrote in 1911.

That may be true, but, as the Weinersmiths remind us, “what emerges from the cradle is not an adult, but a young child, lacking in knowledge, highly excited, and prone to self-destruction. If we plan to leave this place, it is better to do so as adults. Let us spend the difficult years learning and then seek new perspectives.”