They Changed Their Minds about Slavery and Left a…

At first glance, William Turpin and his business partner, Thomas Wadsworth, appeared to be like most other prestigious and powerful white men in late 18th-century South Carolina. They were successful Charleston merchants, had business interests across the state, got involved in state politics, and enslaved numerous human beings. Nothing about them seemed out of the ordinary.

But, quietly, these two men changed their minds about slavery. They became committed abolitionists and worked to free dozens of enslaved people across South Carolina. When most wealthy, white Carolinians were increasingly committed to slavery and defending it as a Christian institution, Turpin and Wadsworth were compelled by their convictions to break the shackles they had placed on dozens of men and women.

In an era when the Bible was edited so that enslaved people wouldn’t get the idea that God cared about their freedom, Turpin left a secret record of emancipation in a copy of the Scriptures, which is now in the South Carolina State Museum.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that this story of faith and freedom is mostly unknown. The two men were, after all, working not to attract attention.

Neither had deep roots in Charleston or close familial ties to its storied white “planter” dynasties. Turpin’s family was originally from Rhode Island, and Wadsworth was a native of Massachusetts who moved to South Carolina only shortly after the American Revolution. Both had public careers and served in the South Carolina Legislature, but their political profiles were not particularly high. Neither of them appeared to give any of their legislative colleagues the sense that they were developing strong, countercultural opinions on one of the most explosive issues of the day.

Wadsworth served in the South Carolina House of Representatives from 1791 to 1797. He represented Laurens District, near Greenville.

Turpin was a state senator representing the parish that comprised the city of Charleston in 1809. Before that, Turpin had served in various public offices, most notably as a commissioner for the East Bay Lottery. This was the same East Bay Lottery that an enslaved man named Telemaque won in 1799. After buying his own freedom, Telemaque changed his name to Denmark Vesey.

The two men were business partners. Their business interests led them to acquire land across South Carolina’s upcountry at what turned out to be just the right time for financial success. In the 1780s, they received several land grants for thousands of acres in both the Ninety-Six and Orangeburg districts. When the cotton gin was invented a few years later, short-staple cotton—which grew well in South Carolina’s upcountry—became a very profitable commodity. Cotton was cultivated with enslaved labor, so the cotton boom also drove up the price of enslaved people.

And Turpin and Wadsworth were invested in that market as well.

This is, so far, a fairly typical story: politically connected and commercially savvy white men making money off a change in the market and ongoing exploitation of labor.

But something else was happening too. Beneath the surface, away from public view, these men were developing different ideas. Wadsworth called it “notions of humanity.”

The first evidence of something different about these men came in 1799, when Wadsworth died of malaria. In his will, he freed nearly two dozen people.

Individual emancipations, or “manumissions,” were not uncommon at the time. These were seen as benevolent final acts, which in no way threatened the regime of slavery or prefigured a general emancipation. In South Carolina, however, the number of people that Wadsworth freed at once was unheard of. In that historical moment, it appeared less like the common cultural practice of deathbed generosity and more like an act of liberation.

The former state legislator also left each family enough property so that they could support themselves in freedom. He left them each 50 acres, livestock, and equipment.

The freed people were scattered across four large districts in South Carolina’s upcountry—Abbeville, Newberry, Union, and Laurens. With the families spread across the upcountry, the scope of Wadsworth’s emancipations appears to have gone unnoticed.

The dying man knew, however, that the people he freed would not fare well in a region where fear and hostility toward free people of color were increasing. So, as part of his last wishes, Wadsworth entrusted them to the protection of his friend, Turpin, and the Bush River Quakers in Newberry District.

Quakers were some of the nation’s first organized abolitionists. A large number of them believed that slavery ran counter to the laws of God. Wadsworth trusted they would look after the freed people as friends, protecting them from anyone who might seek to re-enslave them, and hoped they would treat the Black families as fellow children of God.

This might not be enough to consider Wadsworth and Turpin abolitionists, opponents of slavery itself, but Turpin’s papers show that this one-time enslaver had also spent his money emancipating people. He called them each by name and gave them property. Altogether, Turpin was personally involved in emancipating nearly 60 people.

When he left the South in 1824, he also started to speak out against slavery. Speaking from experience, he began to publicly condemn the “peculiar institution” that had become a way of life in a large portion of the United States and earned many people a lot of money, including Turpin himself.

He wrote former president Thomas Jefferson, urging him to take up the cause of abolition. It was not enough, Turpin told Jefferson, to advocate for freedom on paper. It was “required by God himself” to set the captives free.

Turpin wrote James Madison, too, hoping the founding father who played such a pivotal role in drafting the Bill of Rights would see the importance of ending slavery.

“I have lived more than half a hundred year in a Slave State,” he wrote Madison in one letter, “have ownd [sic] Plantations & Slaves, [and] am well acquainted with the treatment and Disposition of Slaves and of the Laws of all the Southern States. I was so much Convinced of the Evil of Slavery, that we gave 50 [odd] their Freedom.”

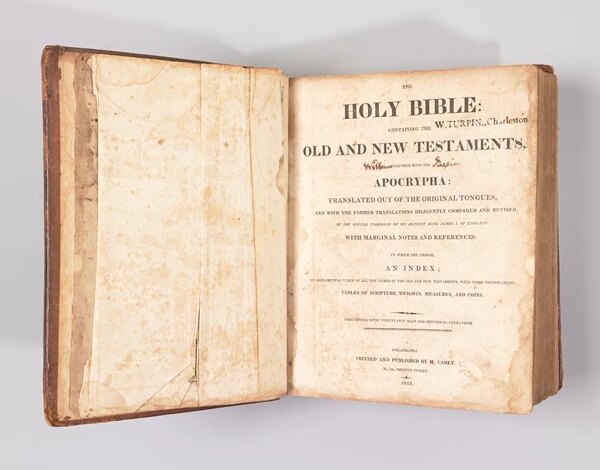

Image: Courtesy of the South Carolina State Museum

This Bible, which dates back to 1815, was once owned by owned by William Turpin, a white South Carolina merchant and enslaver turned abolitionist.

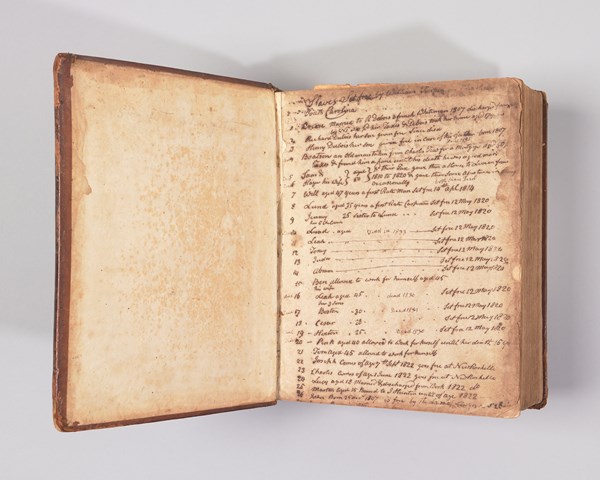

Image: Courtesy of the South Carolina State Museum

One of the first pages in the Bible with a handwritten list of names of enslaved people Turpin freed between 1807 and 1826.

Turpin told Madison that for years, he thought he and Wadsworth were perhaps the only white men concerned with “the cause of the oppressed Affricans.” Then, with a reference to his faith, he prophesied a warning to those who continued to support such oppression that things were about to change.

“Now God has rais’d up 40 millions of consiensious people throughout the world to advocate their cause,” Turpin wrote, “& is dailey adding more to their number.”

Turpin lived long enough to see the abolitionist movement organize in 1830. In 1835, those abolitionists mailed more than 100,000 antislavery tracts to slaveholders, outraging the city leaders where Turpin had once served as a legislator and prompting an attack on the federal mail. It was one of the tremors indicating the earthquake to come.

Turpin’s letters to Madison indicate that he may have already had a sense of what was coming. He believed, after all, that the Almighty was just and that slavery was a horrific sin.

Turpin may have had other motivations besides his faith for converting to the cause of abolitionism. But his Christianity clearly helped compel his personal obedience to what he eventually saw as a righteous cause and also pushed him to acts of contrition.

“I could not Rest,” he wrote, “until I had paid them Wages for the time we held them as Slaves.”

When he died in 1835, Turpin left behind an estate plan that remembered the families that Wadsworth had freed so many years before. He bequeathed them $8,000—not as a gift, according to his will, but “proper renumeration for their time as slaves to Wadsworth and Turpin.”

Turpin also gave his wealth to well-known abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Benjamin Lundy, and Arthur Tappan, and to abolitionist organizations such as the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves and the Genius of Universal Emancipation newspaper.

His obituary described him as an abolitionist and a Quaker.

This past summer, the South Carolina State Museum acquired Turpin’s personal Bible. Within its pages lies the clearest testament to ties between his faith and his conversion to the cause of abolitionism. In the front of the large Bible published in 1815, where religious families of that era often recorded their births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths, Turpin recorded by hand the names and details of those he and Wadsworth freed.

The list gives careful attention to each, treating them with respect.

“Will aged 47 years,” one entry says, “a first Rate man set free 14th April 1814.”

The next reads, “Lund aged 35 years a first Rate Carpenter set free 12 May 1820.”

On the next line is “Jenny 25 sister to Lund …,” followed by more who were set free that day: Leah, Tony, Juda, Abram, Boston, Cesar, Hector, another Leah, and her three sons.

Lists, of course, were common tools for enslavers. They used ledgers like this and the latest techniques of bookkeeping to track the value of the humans they owned and the profits their suffering created. In contrast, Turpin’s ledger recognized their freedom and their eternal worth as children of God.

It also served as proof that these men and women had been set free. Turpin directed that his heirs keep his Bible in South Carolina, knowing the ledger it contained was evidence that he had emancipated these individuals. Legal and social conditions grew more hostile for Black people as the Civil War approached. At least one, Boston, was kidnapped by slave traders in 1825 and re-enslaved. What ultimately happened to him remains unknown.

Indeed, we know too little about the people that Turpin and Wadsworth freed—their lives, their faith, and their stories. There is also much we still do not know about Turpin, Wadsworth, and the abolitionism they kept secret for so long. Turpin’s Bible, however, gives the South Carolina State Museum a place to start. Work is underway to learn more about these enslaved people and their enslavers who changed their minds. And there are plans to reunite descendants from both groups, to physically bring them together with the record in Turpin’s Bible and commemorate this monument to a faith that set captives free.

David Dangerfield is a professor of history at the University of South Carolina Salkehatchie.

Ramon Jackson is curator of African American culture and history at the South Carolina State Museum.