Mamie Johnston: A Brave Missionary in Manchuria

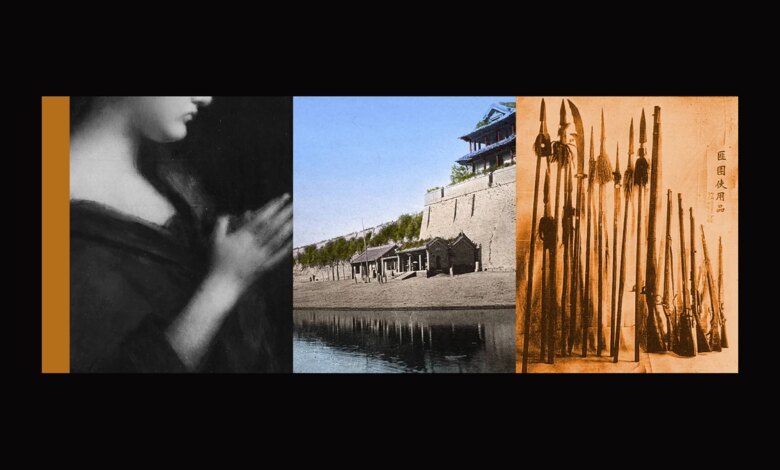

In 1923, 26-year-old Mamie Johnston (韩悦恩, Han Yue-en) was sent by the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, under the sponsorship of its Women’s Missionary Association, to Faku County in northeast China’s Liaoning Province, part of the region then known as Manchuria. Johnston’s adventures in China would span 28 years. She lived through bandit attacks, the Japanese invasion of China, and the rise of the Communist regime.

Thanks to the short memoir Johnston composed 30 years after leaving China, the compelling tales of her missionary experience, including her rustic life in Manchuria and her legendary wit and bravery when dealing with the Japanese, have been preserved.

Fulfilling an early invitation

Johnston’s fascination with China began when she was just eight years old. Isabel “Ida” Deane Mitchell, a female medical missionary from the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, was preparing to travel to Manchuria. She invited the young Johnston to come and join her in China when she was old enough. This invitation remained in Johnston’s heart and would guide her own mission plans nearly 20 years later.

Mitchell settled in Faku, Manchuria, in 1905. The first Western medical doctor ever seen in Faku County, she adopted the elegant Chinese name Qi Youlan (齐幽兰, “serene orchid in the valley”). Tragically, in 1917 she succumbed to an infection she contracted while treating a diphtheria patient, dying at age 38.

Johnston’s dream of joining Isabel in China was shattered. Nevertheless, she applied to become an overseas missionary, setting her sights on either India or China. Ultimately, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland dispatched her to northeast China as a missionary educator.

After arriving in Shanghai by boat in 1923, Johnston proceeded to Beijing to study Chinese at a language school. She then took a position at a teacher training school in Shenyang, the nearest city to Faku.

The following year, she traveled to Faku (known at that time as “Fakumen”) by mule cart. Along the way, she spent a night at a large inn. The compassionate landlady, noticing that Johnston had brought no bedding for herself (local people brought their own quilts and pillows when they stayed at an inn), arranged for her to sleep in the master bedroom.

As Johnston drifted off to sleep amid the scent of opium, which was widely used in China at the time, she heard the landlady say, “This poor girl doesn’t even have a quilt. Although she’s a foreigner, she’s just like us—she knows hardship and has the grits to endure it.” The landlady then covered Johnston with her own quilt, tucking her in like a child. Johnston later wrote, “At that moment, my heart was deeply warmed. This is my country, my people.”

Upon her arrival in Faku, Johnston discovered that the dormitory assigned to her was the very house where Isabel Mitchell had lived. It seemed that the Lord, the master of time, had not forgotten Mitchell’s initial invitation.

Encounters with bandits

A remote area, Faku was often plagued by bandits who broke into homes to kidnap and extort residents. One evening, Johnston and her roommate heard noises on the other side of the wall. Quickly, they rallied the teachers at the girls’ school. Following Johnston’s direction, the teachers rang bells, played the piano, or blew whistles while she and her roommate each grabbed a long stick and charged out of the room, waving their “weapons” in the darkness and playing the part of ferocious foreign devils. Fortunately, the bandits were frightened and retreated, saving the school from calamity.

Before coming to China, Johnston and other missionaries were taught that the church would never pay a ransom to kidnappers, as doing so would only encourage more kidnappings. This understanding prepared her for the possibility of being kidnapped and killed in Manchuria.

In the late 1930s, she and a Chinese female assistant traveled to the China-Mongolia border to visit an established church. One night, while they were resting at an inn, a group of bandits also staying there broke into the room. Confronted by the rough Manchurian brutes, the two female Christians won their respect and trust through their humble and generous attitudes and engaging explanations of the Bible.

The leader of these bandits, known as Da Jia Hao (大家好, “good big family”), even ordered the bandits in the areas the two ladies were passing through to secretly protect them, ensuring their safe arrival at their destination. The only literate steward among the bandits also taught Johnston and her assistant a set of indispensable code words to help her travel safely.

Navigating the Japanese occupation

Following the Mukden incident in 1931, Japan invaded northeast China and established the puppet state of Manchukuo in northeastern China. Japanese soldiers perceived missionaries as rivals, insisting that Christians must venerate the Japanese emperor as a god. Non-compliance resulted in persecution, even death, for both Chinese believers and Western missionaries. Missionaries’ sermons had to be submitted to the police in advance. All correspondence was scrutinized, and a pass, complete with a detailed explanation of the purpose of the trip, was required for travel.

From 1937 to 1944, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland faced financial hardship and could not sustain overseas missionary expenses. Thirty-five missionaries left Manchuria with no replacements, but Johnston stayed. The missionary and educational work in Faku fell squarely on her shoulders.

In addition to compiling teaching materials, she had to be prepared for unannounced inspections by the Japanese army. Any books bearing the word China on the cover or the phrase Published by the Shanghai Commercial Press were destroyed. Johnston and her colleagues clandestinely packed the books and concealed them in a movable space under a window seat in the church. One day, when two Japanese officials conducted a search, they unknowingly sat on that very seat as she reported on the library’s cleanup of unapproved books.

Johnston was under constant surveillance, with police frequently appearing in her classroom. Once, on a train, a man posing as a fellow traveler interrogated her for several hours. Upon arrival at the station, she was immediately escorted to the station’s police office for further questioning. Fortunately, she remained vigilant and gave no grounds for suspicion. Later, a Chinese friend noticed the words completely harmless written next to her name at the police station.

Embodying wisdom and courage, Johnston once helped a Chinese pastor who had been arrested on fabricated charges and placed in a military prison in Tieling, a small city in Manchuria. Unable to obtain a pass for foreigners, she disguised herself as a Chinese woman, donning a leather hat to conceal her golden hair, an old woman’s ragged coat, and a thick brown scarf to hide her face. She quietly took the early-morning bus from Faku to Tieling to deliver a message to Mr. Shang, a Korean translator involved in the pastor’s interrogation, encouraging the pastor to persevere.

On her return trip near dusk, knowing that the police would scrutinize the entry pass, Johnston disembarked near Faku. She traversed wintry fields and crawled under electric fences, arriving home at midnight covered in mud. She undertook this perilous journey multiple times until the pastor was released.

From northeast to southwest China

Following the outbreak of World War II’s Pacific War, Johnston and other missionaries were expelled by the Japanese and forced to leave northeast China. They first sought refuge in Canada, then returned to Ireland six months later before heading to India and finally returning to China.

By 1945, northeast China was under Communist control, so Johnston was dispatched to Kunming in Yunnan Province, southwest China, to establish Sunday schools for the local churches and to oversee kindergartens and teacher training.

In late 1949, Kunming fell to the Communist government. The church began to propagate the notion that accepting foreign aid was treasonous and that missionaries were potential spies. Pastors were compelled to have congregations chant anti-foreigner slogans during their worship services. As the only foreigner in her church, Johnston was in a risky situation. After the pastor chanted the slogan, he would console her with a hymn that said, “In Christ there is no east or west.” She recognized that she had become a burden to the church, but she couldn’t simply leave China. The decision to stay or leave was no longer hers to make but was dictated by government policy.

When she was finally permitted to leave Manchuria after numerous obstacles, Johnston was escorted by various military personnel on a journey that took her from relative comfort to abhorrent conditions. She traveled via military planes and ships, staying first at hotels and later, temporary prisons. Her journey took her from Chongqing to Wuhan, Hankou, Guangzhou, and eventually Hong Kong. She transitioned from being neatly dressed to being ragged, from eating freely to dieting on rationed food, and from sharing a room with people to sharing a room with rats. She was forced to witness soldiers shooting a car full of prisoners. This final trip across China was like hell on earth.

When guards stormed into Johnston’s cell in the middle of the night, shining a torch in her face and shouting, “You are now in the hands of us Communists!” she felt unexpected joy and strength. She was no longer fearful but filled with profound peace and certainty that, like all Christians, she was safe in God’s hands. It was a peace she had felt before during her many years in China. The notion that she was worthy of suffering for Jesus imbued her then, as it always had, with genuine love and compassion, equipped her to live joyfully and patiently with those around her, and gave her a sense of calm and freedom that transcended life and death.

Johnston was expelled from China by the new Communist government in 1951. Upon returning to her hometown in Ireland, she summed up her adventures in an interview, stating with deep emotion, “China: that is my place of dedication.”

Su La Mi is a Christian writer and editor who taught liberal arts at a university in northeastern China.