Inside the ‘Secret World’ of Global Evangelism to Muslims

In a 2007 article, CT described British church historian Andrew Walls (1928–2021) as “the most important person you don’t know.” Among his greatest achievements was helping turn the attention of Western scholars to the remarkable growth of Christianity in the Global South. Walls’s work on what he then called “non-Western Christianity” was amplified by the efforts of David B. Barrett (1927–2011), whose groundbreaking research on global religious statistics produced the World Christian Encyclopedia, coedited by Todd Johnson and Gina Zurlo.

We now know that the demographic center of Christianity shifted to the Global South during the 20th century in dramatic fashion, and we also know a lot more about how it actually happened. Evangelicalism, as one of the fastest-growing demographic blocs within global Christianity, has contributed significantly to these transformations.

Today, more than 77 percent of the world’s evangelicals are Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans. Even if a significant number of American evangelicals may favor some form of Christian nationalism (though the numbers are likely exaggerated), and even if a majority of white American evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, what often goes unstated is that the vast majority of the world’s evangelicals are neither white nor American. Evangelicals around the world are not united on matters of politics and race, but they lay great stress on the Bible, the central message of the Cross, and man’s need for conversion.

Evangelicalism, then, is plainly not an American movement. The vast majority of the world’s evangelicals live in the Global South, and they are actively engaged in sending missionaries to the ends of the earth. The World Council of Churches began using the language of “witness in six continents” in the early 1960s to describe how new mission centers were now established on every continent in the world.

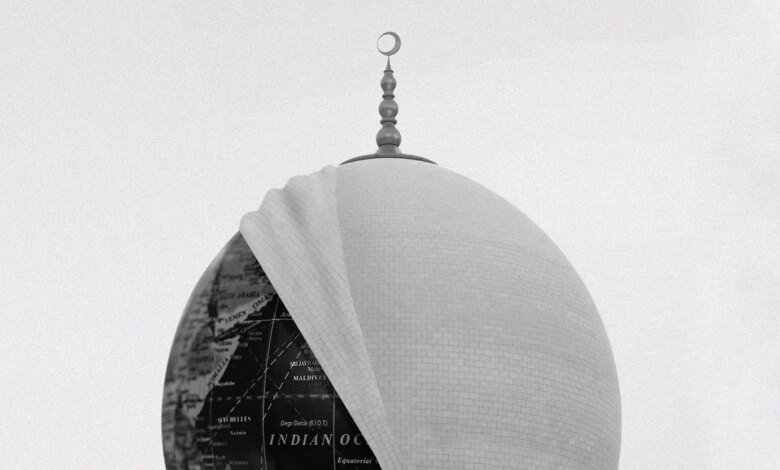

When evangelicals gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1974, for the First International Congress on World Evangelization, they observed that the dominant role of Western missions was fast disappearing. In the 1980s, Luis Bush, an unassuming evangelical from Argentina who became an influential mission leader, coined the expression “the 10/40 Window.” The name referred to the regions of North Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, concentrated in a single geographic rectangle between 10 and 40 degrees north of the equator.

Bush was hoping to mobilize evangelical missionary movements from Africa, Asia, and Latin America into places Western missionaries found it harder to reach. He made it clear throughout the 1990s that these missionary efforts would be led not by Americans but by Christian leaders in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Americans popularized “10/40 Window” language in mission circles, but Bush was holding massive gatherings in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to mobilize missionaries from the Global South. Today, nearly half of the world’s full-time cross-cultural missionaries are being sent out from the Global South, with countries like Brazil, South Korea, and India figuring among the top senders.

Rare access

Adriana Carranca describes some of these global transformations in her new book Soul by Soul: The Evangelical Mission to Spread the Gospel to Muslims. Carranca is a Brazilian writer who has worked as a war correspondent and investigative journalist in some of the most difficult places in the world.

Educated at Columbia University and the London School of Economics, she has traveled widely in Africa and the Middle East, covering events like the American-led invasion of Afghanistan, the Peshawar church bombing in Pakistan, the Lord’s Resistance Army uprising in northern Uganda, the Islamic revolution in Iran, and the Arab Spring in Egypt. While Carranca was working in conflict zones and refugee camps, she began meeting evangelicals looking to reach Muslims with the gospel.

As a secular journalist who had spent time in American contexts, Carranca knew something about American evangelicalism. But what she discovered while working in Africa and the Middle East surprised her. Most of the evangelical missionaries she met were not from the United States. Instead, they were being sent out to the Muslim world from places like Brazil, Columbia, Mexico, South Africa, China, and South Korea. The evangelical mission to Muslims, she learned, was emanating from the Global South.

In 2008, Carranca was in Kabul covering the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. Here, she first heard about significant numbers of Muslims who were converting to Christianity. This evangelistic endeavor, she discovered, was being led by an evangelical, Luiz, who hailed from her home country of Brazil. He was part of a network of other evangelicals from the Global South.

Eventually, Carranca convinced Luiz and his wife, Gis, to share their personal stories and to introduce her to other evangelical missionaries working in different parts of the Muslim world. To better understand the growing number of evangelicals she was meeting in Africa and the Middle East, she began reading works on global Christianity by historians like Philip Jenkins, Mark Noll, Dana Robert, Lamin Sanneh, Brian Stanley, and the aforementioned Andrew Walls.

Through her friendship with Luiz and Gis, Carranca grew more familiar with the world of evangelical missionaries who were serving on the ground in places like Afghanistan, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Pakistan, and Syria. She met the occasional American or European, but the vast majority of missionaries she encountered were from Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria, China, Romania, and South Korea.

During her travels, Carranca gained rare access to what she called the “secret world” of Christian missionaries evangelizing Muslims. She also learned about the influence of Luis Bush and traveled to meet him in Indonesia, where he was mobilizing thousands of missionaries from Asia to preach the gospel to Muslims.

Carranca’s long-form journalism is serious, intimate, and gripping. Though not a believer, she confesses that she came to admire the evangelicals who became her friends. The book introduces readers to Luiz and Gis and their coworkers from South Africa, Brazil, China, and South Korea, and talks about their daily lives, their love for soccer, and the joy they find in spending time with Muslim friends.

Carranca’s narrative includes riveting eyewitness accounts of terrorist attacks, drone strikes, police inquiries, church bombings, and the martyrdom of local Christians in Pakistan and Afghanistan. In one powerful anecdote, she talks about the murder of a missionary family she befriended in Afghanistan, killed by the Taliban in a brutal shooting. She flew to Pretoria, in South Africa, to attend their funeral services, where their graves were marked with a popular refrain echoing Tertullian’s words about the blood of martyrs: “They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.”

Polycentric Christianity

Soul by Soul introduces readers to some of the new faces of evangelicalism—and they are almost nothing like Barbara Kingsolver’s unflattering caricature of a failed missionary to the Congo in her popular novel The Poisonwood Bible. Rather than fictional white Southern Baptists from Georgia who are more misanthropes than missionaries, Carranca gives us real people, unmarked by what she calls the “arrogance and triumphalism” that has sometimes been associated with Western missionaries.

Her book does have some potentially misleading aspects. It begins with a concise history of Christian missions, which is largely confined to the history of American evangelical missions. This tends to give an impression of an American-led movement that runs counter to the book’s broader thrust.

Relatedly, Carranca seems to hold the view, sometimes stated subtly, that Americans are still somehow clandestinely leading the new missionary efforts now rising in the Global South. This is a highly contested interpretation. It misunderstands the polycentric nature of Christianity and it diminishes the important new role being played by rapidly growing evangelical movements outside the West. American evangelicals continue to support global missions from everywhere to everyone, but evangelicals in the Global South are often the ones leading the way.

Carranca’s work concludes by observing that American evangelicals have been among the strongest supporters of military intervention in the Middle East, even though these wars often complicate the lives of Christians in Africa and Asia and hamper the work of evangelical missionaries there. She also points out the tension between American evangelical support of Trump’s efforts to suppress migration from certain Muslim-majority nations and a simultaneous support of efforts to evangelize Muslims.

In these and other ways, Soul by Soul offers a prophetic challenge for American evangelicals who are enamored of an “America first” mindset. “Ultimately,” she writes, “American Protestant evangelicals will need to choose whether to be citizens of a nation or part of the global, diverse, and borderless kingdom of God.”

F. Lionel Young III is a senior research associate at the Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide. He is the author of World Christianity and the Unfinished Task: A Very Short Introduction.