ESPN reporter Lauren Sisler lost her mom and dad to overdoses

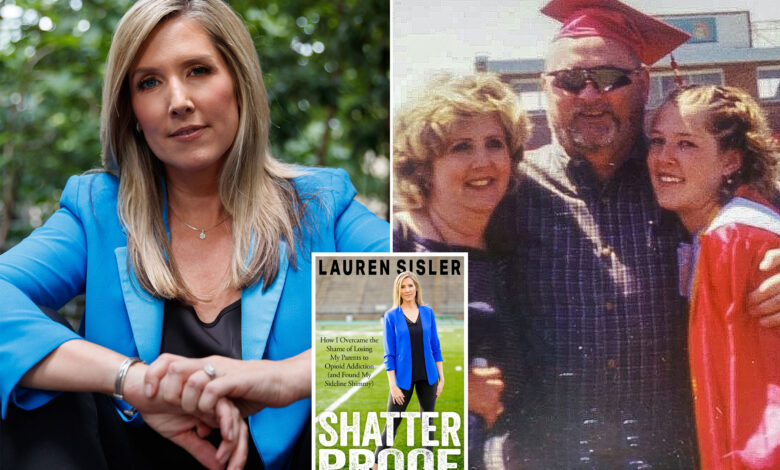

College football fans know ESPN sideline reporter Lauren Sisler for her sunny personality, incisive interviews and exuberant dancing during games — what she calls her “sideline shimmy.”

But the 39-year-old Birmingham resident has a painful history that she kept hidden for nearly two decades: When Sisler was in college, both her parents died of drug overdoses.

Her mom, Lesley, went first. She ingested an entire pack of fentanyl and was found unresponsive on the front porch of their Virginia home. Sisler’s dad, George, did the same hours later, his body found on the kitchen floor.

The night they died in 2003, police found empty prescription bottles with 348 OxyContin pills, 60 oxycodone pills and 82 other painkiller tablets. Later, Sisler’s aunt and uncle found wrappers and sticks from pain-relief suckers, as well as a razor blade and pill crusher under the sink.

A lockbox where they kept a stash of super-strong fentanyl patches was empty: Mom and Dad had finished a two-week supply in a matter of days.

They had kept their addiction a secret from their children, the rest of their family and their community.

As Sisler told The Post: “Everyone was in absolute shock.”

But now she’s ready to tell the story. Her new book, “Shatterproof: How I Overcame the Shame of Losing My Parents to Opioid Addiction (And Found My Sideline Shimmy,” is a powerful, scary, but ultimately empathetic and redemptive look at prescription drug abuse.

Sisler was her boundlessly optimistic self when she met The Post last week on the High Line, talking about her 15-month-old son, Mason, and their plans for Halloween. (Sisler, who is married to John Willard, who owns a roofing company in Birmingham, Alabama, wants to dress Mason and the family’s yellow Lab, Magnolia, as M&Ms. “Wouldn’t that be cute?” she cooed in her Southern accent.)

Over Coke Zeros at a Chelsea cafe, she got emotional as she explained her decision to come clean about her parents’ past.

“I realized that holding in their secrets and holding in the shame [they had surrounding their drug use] didn’t serve my parents well,” she said. “And it didn’t serve those around them well.

“And then as I started telling more people the truth, I realized that people who loved my parents didn’t think any differently of them. If anything, they found peace in knowing what happened, and they didn’t love them any less, didn’t love me any less.”

The truth could even, she discovered, save lives.

“I realized, Hey, I can be open about this, and while it doesn’t change who [my parents] were or doesn’t change who I am, it can ultimately help somebody who is struggling.”

Sisler had a happy childhood. She recalls games of flashlight tag in the summers in their Roanoke suburb with her older brother, Allen, and watching local stock car races with her family. “Sports was in the blood,” she said, adding that she got into gymnastics early. “My parents had to take me to the ER too many times because of all the jumping on the beds.”

Sisler’s dad, known as Butch, coached Little League and recorded her gymnastics routines with his camcorder. Her mom, Lesley, prepared a hot meal every night. “I always felt loved and taken care of,” Sisler said. “Were we spoiled? Yes. Were we disciplined? Sometimes. We probably could have been disciplined a little more, but we were very fortunate to have parents who would do anything for us.”

Butch could be erratic. Sisler remembered him going on weekend benders a couple times a year when she was a child; he would get so drunk that he would make extravagant purchases that made her mother angry. Yet no one ever said he was an alcoholic. “I would never think Dad’s got a problem,” Sisler said. He would go on his bender, regret it, and apologize and then stay sober for six months or so. “We would just go about our life.”

Sisler believes that their family situation began to deteriorate when they moved from Roanoke to the country when she was a teen. The house they built ended up costing much more than initially budgeted, and her mother’s buzzing social life got a lot quieter. Later, Lesley was diagnosed with degenerative disc disease and had several operations. Butch, meanwhile, had back surgery.

They were prescribed medication to deal with the pain — and then saw a pain specialist who kept increasing their doses of narcotics as the family’s finances spun further out of control. It was, Sisler writes, “Their means to help them cope with their chronic pain and depression … [but] no one in our family was privy to their struggle.”

Even when her father was rushed to the emergency room the night before Thanksgiving in 2002, Sisler had no idea he had sucked on a cold fentanyl patch — a trick he read on the Internet when searching what would get him the quickest, highest high. Sisler thought he had just mixed up medications and had a heart attack.

“I just could not accept that my parents were ‘drug addicts,’” she said.

On March 23, 2003, she was sleeping in her dorm room at Rutgers University, where she was a freshman on a gymnastics scholarship, when her phone rang at 3:30 a.m.

It was her father. He sounded distressed. “Lauren? I need to talk with your brother,” he said.

“What’s wrong?” Sisler asked, groggy and confused.

“I’ll call you back in a few minutes,” Butch said after Sisler gave him her older brother’s number.

When he called back 60 seconds later, he told her the horrifying news.

“Lauren, your mom died,” he said.

Sisler could not believe what she was hearing. She had just spoken with her mother before going to sleep. She seemed fine. She was 45, healthy, vibrant.

Sisler slumped to the floor. The next thing she knew her roommate was shaking her, saying, “Wake up! You’re having a nightmare!”

As she was in the airplane flying back home, she looked out at the clouds and thought, This is where my mom is now. My mom’s in heaven. Then she wondered if her dad was there too.

“But then I thought, there’s no way he’s gonna die too,” she said. “There’s no way the absolute worst can happen, right?”

When her uncle and cousin arrived at the airport instead of her father, she knew that the absolute worst had happened.

When she saw her parents in their caskets, she hardly recognized them. “They looked so sad, so sad and broken,” she said, her eyes welling with tears. “And I was fearful that was going to be the vision I would have of them for the rest of my life — these two people who were so joyful and full of life.”

Sisler initially refused to believe that her parents had died from a drug overdose. She told people that her mother died of respiratory failure. She said her father, who had cardiovascular problems, had a heart attack shortly after. He just “couldn’t live without her.”

She did not read the toxicology reports from her parents’ deaths until 10 years later.

Sisler went back to Rutgers and switched her major from pre-med to communications, with the goal of getting into broadcasting. Her jobs as a local reporter for news stations in New Jersey, Virginia and Alabama brought her up close with death and suffering. Slowly, she began to seek out the truth.

“At first, any time my aunt, for instance, would bring up my parents and their death, I would just shut her out or defend them,” Sisler said, adding she felt like she was the caretaker of their legacy. But she saw how the truth set the people she interviewed free.

She reconnected with the EMT who went to her parents’ house twice that fateful night, and with the deputy sheriff who found her father’s body. She poured through medical and financial reports. And she felt “relief.”

“The truth really does set you free,” she said.

Sisler began speaking at schools, conferences and nonprofits about opioid abuse. She realized that more people than she ever could have imagined have suffered from prescription drug addiction or had a loved one who suffered from it.

And she thinks her parents would be proud of the way she has handled their legacy.

“No matter how much pain and sadness they were going through when they left, I truly believe they are here in this moment, just smiling so big, because they know their story is making an impact,” she said. “I truly, truly believe from the bottom of my heart that their story is saving lives.”