A new book reveals how the complaint was made public on Facebook

One afternoon in December 2020, Wall Street Journal reporter Jeff Horwitz drove to Redwood Regional Park, just east of Oakland, California, for a mysterious meeting.

For months, he had been working on a story about Facebook, though with little luck finding anyone from the company willing to talk. But then she approached Frances Haugen.

On paper, she didn’t seem like the most obvious candidate for whistleblowing. Haugen, 35, a mid-level product manager on Facebook’s Civic Integrity team, had only been on the social network for just under a year and a half. But she was anxious.

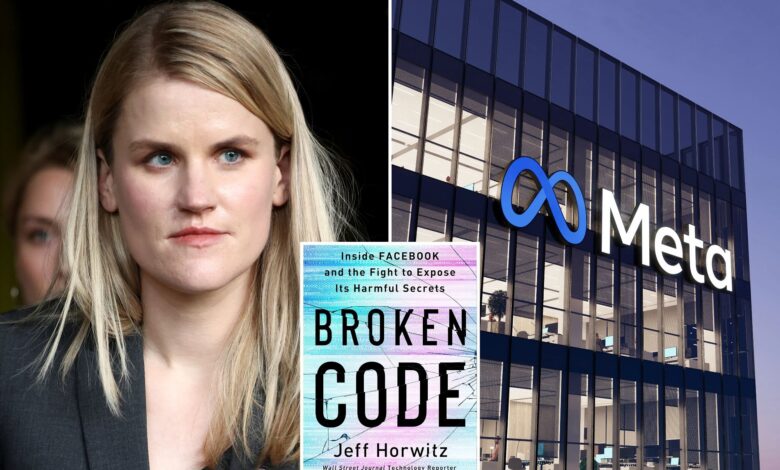

“People needed to understand what was going on at Facebook, he said, and he had been taking some notes that he thought might be helpful in explaining it,” Horwitz writes in his new book, “Broken Code: Inside Facebook and the Fight to Expose Its harmful secrets” (Doubleday).

Haugen didn’t want to talk via email or even on the phone, insisting it was too dangerous.

Instead, he suggested meeting on a hiking trail for privacy; He even sent the address to Horwitz through an encrypted messaging app.

They walked for nearly a mile among the California coast redwoods, looking for a place isolated from hikers and runners.

Haugen’s paranoid maneuvers were worth the wait.

He had found evidence that “Facebook platforms eroded faith in public health, facilitated authoritarian demagoguery, and treated users as an exploitable resource,” the book says. But she wanted to do more than just smuggle out a few lost documents.

She was “contemplating spending months inside the company for the specific purpose of investigating Facebook,” Horwitz writes.

Neither of them could have anticipated how far down that rabbit hole would take them.

Over the next few months, Haugen would bring Horwitz “tens of thousands of pages of confidential documents, showing the depth and breadth of the damage being done to everyone from teenage girls to victims of Mexican cartels,” Horwitz writes. . “The uproar would plunge Facebook into months of crisis, with Congress, European regulators and average users questioning Facebook’s role.”

At first, Horwitz was intrigued but cautious. Haugen’s sincere belief that “if he didn’t expose what was known inside Facebook, millions of people would probably die” struck him as quite grandiose and melodramatic.

Still, he had nothing but faith in Haugen’s intentions. She wasn’t just a disgruntled employee, but someone who truly believed that exposing Facebook was the only way to save it.

Originally from Iowa with parents who were college professors, Haugen had studied electrical and computer engineering at Olin College before heading west to Silicon Valley in the mid-aughts, full of optimism about what social media could achieve.

She “reflexively embraced the idea that social media was good for the world or, at worst, neutral and entertaining,” Horwitz writes.

Haugen was hired by Facebook in 2019 for a noble mission: to study how misinformation was spreading on the site and what could be done to stop it. His team was given only three months to come up with a viable plan of action, a timeline Haugen knew was implausible.

When they failed to offer easy solutions in a short period of time, senior management reviewed them poorly.

But Haugen was undeterred and had questions, such as why there were so many employees at Facebook.

struggling? They were understaffed, had absurd deadlines, and were more often than not ignored when they came up with real, albeit difficult, ideas about how to improve the platform.

“I was surrounded by smart, conscientious people who were discovering ways to make Facebook more secure every day,” Haugen told the author. “Unfortunately, security and growth typically trade off, and Facebook was not willing to sacrifice even a fraction of a percent of growth.”

Samidh Chakrabarti, former leader of Facebook’s civic integrity team, assured Haugen that most Facebook workers “accomplish what needs to be done with far fewer resources than anyone would think possible,” a revelation that was intended to be inspiring but which Haugen found disturbing.

It was a corporate philosophy shared by many authority figures in the company. “Building things is a lot more fun than making them safe and secure,” Brian Boland, longtime vice president of Facebook’s Advertising and Partnerships divisions, told the author of Facebook’s unofficial view of the world. “Until

“If there is a regulatory or press problem, it is not addressed.”

When Facebook engineers were asked in 2021 what their biggest frustration with the company was, they shared similar concerns. “We perpetually need something to fail, often spectacularly, to generate interest in fixing it,” reads one response. “Because we reward heroes more than people who avoid the need for heroism.”

Haugen and Horwitz began meeting regularly and moved into the author’s backyard in Oakland. He bought her a cheap phone to take screenshots of files on his work laptop. One of those files was an internal analysis of Facebook’s response to the January 6 riots, illustrated with a cartoon of a dog on a firefighter.

hat in front of a burning Capitol building.

Haugen and his team were tasked with identifying how Facebook could stop or at least deter users from using the platform to fan the flames of conspiracy theories like Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” election denial in the future.

They created what became an “information corridor,” in which connections were drawn between ringleaders, amplifiers, and “susceptible users,” those most likely to be influenced by radicalism. There were 12 teams within Facebook, working not only on how to take down user groups that spread misinformation, but also how to “inoculate potential followers against them,” Horwitz writes.

This did not sit well with Haugen, a progressive Democrat with libertarian leanings.

Facebook had “shifted from targeting dangerous actors to targeting dangerous ideas, building systems that could quietly stifle a movement in its infancy,” Horwitz writes. “I had images of George Orwell’s thought police.”

Although Haugen’s main focus on Facebook was how misinformation was spread, he stumbled upon other damning evidence on a whim. Curious about how Instagram, the platform purchased by Facebook in 2012, affected teens’ mental health, she found a 2019 presentation by user experience researchers that came to this heartbreaking conclusion: “We make teens’ body image problems worse.” one in three adolescents. “

There was also documentation that Facebook knew its site was being used for human trafficking, but did nothing to stop it.

“The bigger picture that emerged was not that vile things were happening on Facebook, but that Facebook knew about it,” Horwitz writes. “He knew the scope of the problems on his platform, he knew (and usually ignored) the ways he could address them, and, above all, he knew how the dynamics of his social network were different from those on the open or offline Internet. line. life.”

On Haugen’s last day as a Facebook employee, May 17, 2021, she decided to go out with a bang.

He had already collected 22,000 screenshots of 1,200 documents over the course of six months. But while Horwitz waited outside his apartment in Puerto Rico, where he had moved from California, with a taxi ready to flee, Haugen downloaded the company’s entire organizational chart, “a horde of information that surely represented the largest leak in the history of the company”. ”Horwitz writes.

In September 2021, the Wall Street Journal finally published the Facebook files, which Horwitz spearheaded along with other journalists. Haugen gave a damning interview to “60 Minutes” and testified days later at the Capitol.

“Facebook wants you to believe that the problems we’re talking about are unsolvable,” Haugen told the committee, before explaining exactly how the biggest social media giant on the planet could solve all of those problems.

It’s what sets Haugen apart from other whistleblowers. She wasn’t simply trying to point out where her former employer had gone wrong, burning the bridge while she dumped secrets. Her optimism about social media may have been deflated by her experiences on Facebook, but she also believed that it was not necessary to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

It’s debatable whether anything at Facebook has changed since his testimony. But Haugen continues to fight to fix social media’s problems, not just expose them. Last year he launched a nonprofit, Beyond the Screen, dedicated to documenting how big tech companies are failing to meet their “ethical obligations to society” and devising plans to help them correct course.

Haugen hasn’t had any interaction with Facebook since that last day, but he left a goodbye message on his way out the door. Just before he closed his laptop, after downloading files that would prove the company valued its users’ undivided attention above their souls, he wrote a goodbye message that he knew Facebook’s security team would stumble across. inevitable forensic review.

“I don’t hate Facebook,” he wrote. “I love Facebook. I want to save him.”