Russia’s first manned space flight was basically a PR stunt

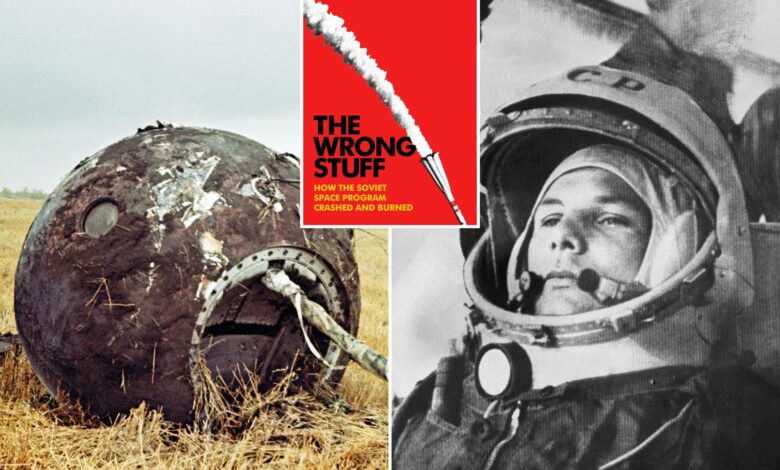

The “space race” of the 1950s and 60s conjures images of the gleaming Sputnik satellite, Soviet scientists in crisp white coats and sharp-nosed rockets rising into the sky with fiery splendor. But, the reality of the USSR’s space program — which narrowly beat the US to send the first man to space — was far more down-to-earth writes John Strausbaugh in his new book, “The Wrong Stuff: How the Soviet Space Program Crashed and Burned” (out now, PublicAffairs). Strausbaugh paints an amusing portrait of rockets and spacecrafts held together with little more than bubblegum and shoe strings — and tight-lipped publicity campaigns. In this excerpt, he writes of Yuri Gagarin, the first Russian cosmonaut sent into space.

On the morning of April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin fell out of the sky onto a quilt of farmland growing wheat and rye in the Russian village of Smelovka. He unhooked his parachute and strolled, waving, toward a woman and her five-year-old granddaughter who were weeding a potato patch.

“Have you come from outer space?” the woman asked him.

“As a matter of fact, I have!” he answered with a grin. And then, because his radio had broken and he needed to report in, he asked where the nearest telephone was.

The first human being to go into space couldn’t report his achievement because he couldn’t find a phone.

In 1959, lead Soviet rocket engineer Sergei Pavlovich Korolev cannily offered to build a space vehicle that could do double duty, with a pressurized cabin that could carry either humans or spy cameras and safely return them to the ground.

Even though the first cosmonauts would mostly be passengers on their missions, all the candidates originally chosen for the program were Russian air force pilots. The thinking was that jet pilots had proven dexterity and excellent vision, and some experience with such spaceflight-like conditions as g-loads and hypoxia, not to mention ejection seats.

Lieutenant Yuri Gagarin, a 26-year-old MiG pilot, was one of the few chosen to train for the early missions. Proud to serve and eager to please, Gagarin was a small young man, five-foot-three, with bright blue eyes and an ever-ready grin that belied his rough upbringing. He was born in 1934 in an ancient hamlet called Klushino in Russia’s Smolensk region.

Some of the training was similar to what the Mercury astronauts were going through in the United States.

Gagarin endured high g’s in a centrifuge, which once spun out of control, nearly killing another trainee. He experienced momentary weightlessness in parabolic aircraft flights, and practiced in a mock-up of the capsule (not that there was much to practice).

Since it was quite possible that on reentry he might come down way off target, he did wilderness training; dropped into an isolated area of forest or mountains, he had to make his own way back to civilization.

There was also intensive parachute training, an eye-socket rattling “vibration seat” to be endured and, worst of all, the isolation chamber, aka the Chamber of Silence and the Chamber of Horrors. His American counterparts, training in the US to go to space aboard the Mercury, also hated theirs.

It was a soundproof box mounted on shock absorbers in the middle of a laboratory. The walls were 16 inches thick. It was furnished with a replica of the Vostok seat, a small bed and table, and an electric hot plate for heating up food. When the door closed you were plunged into total silence.

The point was to test trainees’ ability to withstand the complete seclusion of a long spaceflight — say, to the Moon and back. It was an exercise in harrowing loneliness, sealed inside for up to fifteen days, knowing they were under 24/7 scrutiny.

For long periods they endured silence so total, so profound, that their heartbeats boomed like cannons. Then suddenly lights flashed and music blared and they were supposed to solve complex math problems while an amplified voice thundered the wrong answers at them.

But worst of all were the oxygen deprivation tests, when the air supply was gradually pumped out while the trainee wrote his name on a pad, over and over.

Gagarin survived by keeping up a positive attitude and appearance, cheerfully holding one-sided conversations with his silent observers, singing little ditties he made up about objects in there with him — the hotplate, the squeeze tubes of cheese, even the electrodes monitoring him.

At 9:07 a.m. on April 12, Gagarin felt the engines kicking in and called out, “Poyekhali!” (“Let’s go!”) He launched smoothly into a warm, cloudless blue sky. Everyone in the control bunker started to breathe again.

But the first glitch came soon. The rockets didn’t cut off when they should have, and shot Gagarin up to an altitude of 203 miles instead of the planned 143. Soon though he settled into his single 108-minute orbit.

Cosmonauts were not allowed to tell even their families of upcoming missions, so any deadly failure could be covered up. At one point the engineers on the ground triggered the retro-rockets to brake for reentry. The rockets burned as planned — then things went wrong again.

“As soon as the braking rocket shut off, there was a sharp jolt, and the craft began to rotate around its axis at a very high velocity,” Gagarin would explain the next day. “Everything was spinning around.”’

Behind the Vostok sphere that held Gagarin was an equipment module with the braking rockets, oxygen tanks, and batteries. This was supposed to detach when the retro-rockets cut off. It had not.

A thick cord of electrical cables kept them “tied together, like a pair of boots with their laces inadvertently knotted,” Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony write in Starman, their biography of Gagarin. “The whole ensemble tumbled end over end in its headlong rush to earth.” If the two modules collided as they lurched around, Gagarin would likely be killed.

Then came a bit of luck. The cables burned through, and the capsule broke away from the rocket pack. Unfortunately, that made it start spinning so violently that Gagarin nearly blacked out.

“The indicators on the instrument panels went fuzzy, and everything seemed to go gray,” he’d later report.

As the capsule dropped through denser air the fire burned out and the spinning eased somewhat. Gagarin could see blue sky out the charred porthole. The ejection device was supposed to be triggered automatically at seven kilometers, but the indications are that Gagarin decided not to wait.

Apparently he blew the hatch manually and ejected early. There was a rumor that he’d panicked. But maybe in the midst of being tossed around in a superheated metal ball he made the logical decision not to trust the faulty hatch and not to bet his life that the automatic ejection device would function properly.

As he drifted down under his parachute, Gagarin had no idea how lucky he was that his parachute opened: Later it would come to light that the engineer in charge of testing cosmonaut parachutes failed to either report or fix a problem with them snagging on an antenna as they deployed.

Two kilometers from where Gagarin touched down, children from the village saw the Vostok ball hit the ground, bounce a little, roll a little, and come to rest on its side near the river.

Scorched black from the heat of reentry, its open hatch gaping, it didn’t look like an historic victory. It looked like an old and battered object raked out of a tragic fire and then discarded.

Gagarin went into the history books as the first human to orbit the Earth, but in fact where he dusted down was a bit short of a full orbit. The real first human to fully orbit the planet would be Gherman Titov, but he would spend his life relegated to being Gagarin’s also-ran.

The whole world cheered the Soviets’ achievement. The whole world, except the United States. For NASA, Gagarin’s triumph was even more demoralizing than Sputnik had been. They were just weeks away from putting the first Mercury astronaut in space, and once again the Soviets had trumped them.

But, the Soviets covered up the fact that Gagarin landed separately from his capsule and about 500 kilometers away from his target, the launch site at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. They also concealed the fact that Gagarin nearly died returning to Earth.

Hints and rumors would circulate, but the facts wouldn’t be widely known in the West until 1996, when, oddly enough, an auction of Soviet memorabilia at Sotheby’s in New York blew the cover.

Excerpted from “The Wrong Stuff: How the Soviet Space Program Crashed and Burned” by John Strausbaugh. Copyright © 2024. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.